(Originally found among the text files at PuebloHeritageAssociation.org November 7, 1999)

We all have our own unique tipping points. I guess mine is a little further down than most people’s, although not by much. I try and keep it restrained, deep where it can’t show itself. Relax, breathe, open your eyes, take it all methodically in. Tomorrow’s a new day.

Life In Petomele is hard, but then life in any forgotten region is hard. I remember when I was five, and I heard my mother screaming downstairs. On and on, hours on end, until finally from down the street I heard the distinct noise of an ambulance siren, and then after some quiet murmurs and the slam of the doors, an hour of silence. And I remember sitting there, all still, not moving once for the duration of that hour.

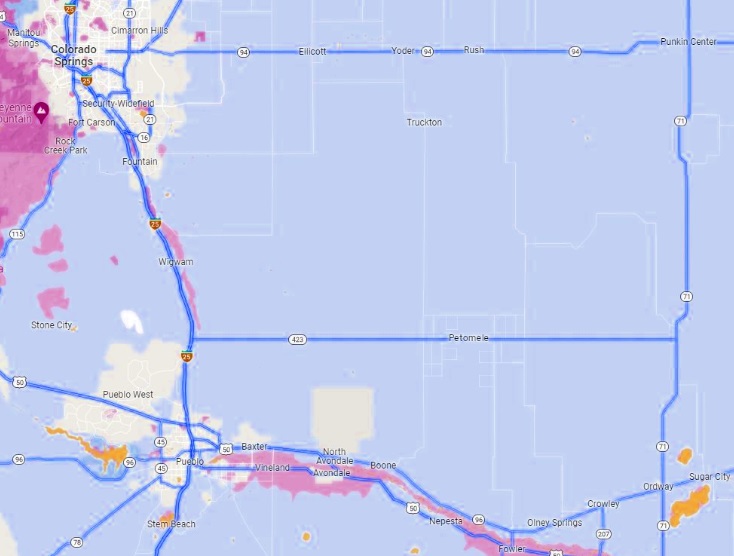

My other mom had caught her index finger in a piece of farming equipment, till it had been reduced to a bloody stump, and it took an hour for the medics to arrive from Colorado Springs. That’s how far out Petomele is. Response time has improved since then, though not by much.

It was tough coming of age under those conditions, out where the grass sways and the land is nothing but dirt, and in summer you see these strange things moving out across the vastness- like ships, billowing sails framed in silhouette, ten times larger than a covered wagon. And all you have to keep you safe is one farmhouse on the outskirts of your little nothing town with one lit window and a handful of buckshot inside which you’re not even confident in using.

My parents were the only lesbians in town, they had adopted me shortly after my birth- although whenever I asked either of them, they said they’d rather not discuss it. They kept to themselves, generally, spent a lot of time doing chores and keeping the bills paid. Didn’t go into town often, for obvious reasons, and when I turned 10 they had me get the groceries each Friday. The rest of our food was home grown.

You may never have been to Petomele, so you don’t know how it is to walk up Main Street, turn onto Canal, and then into the cool air-conditioned aisles of 3rd Avenue Market, with the checkerboard floor and the low ceiling and the strange easy listening pieces drifting over the radio as the clerk stands behind the tin of gumballs digging his frail digits into the morning edition of the Petomele Courier.

You have nothing to compare to a soft, distant Petomele night. Crickets going at it in the trees, a million of them, breeding, festering, filling every cottonwood with their ilk, screaming to high heaven. One big rig out on Highway 423, its engine motoring off into nothing. And all the lanes and streets, all dark houses, nobody home, all gone.

That’s Petomele. I know it well.

There are times when this place doesn’t feel like it should exist. As if every waking day is only a dream, and every period of sleep is a brief intermission, as if everything I see is just a picture being flashed onto the screen of an empty movie theater. Long fence in front, fading out into the distance, neglected and rusting, and the mailbox that never gets any mail.

You don’t know Petomele. You might have passed through it once, might have remarked on it while you were in it, but then it left your rearview mirror and like a million other small, insignificant towns out here on the far side of nothing, it left your memory. You don’t see what goes on here, you haven’t seen those large, moving things out in the night. Dark triangles, each a mile high, shifting and making reverberant creaking noises. You didn’t stick around long enough for that.

My mom with the missing finger is the only one left now, she comes out to visit me every so often, we’re separated by miles of county road and she’ll drive up in her SUV, shamble to the front door. We’ll exchange a few words, she’ll look at me and it’ll seem like she’s about to say something, but she won’t. Because I don’t know her all that well. Not as much as I wish I did. I think she’s content to leave me in the dark about certain things.

At night I still hear her screaming, screaming as that vicious machine tears away at her hand, a stump of bone, flesh exposed to the dry high plains air and the shock nearly causing her to pass out- blood over her apron, blood over everything, blood running red and deep in rivers of scarlet fugue. Face caught in one horrible expression, nothing but the utmost agony.

A face I never saw, because I was up in my room sitting down, staring at the wall ahead of me while it closed in all around, like in one of those old adventure serials, and the sun beat on my forehead and a stray mosquito lapped at my arm. I didn’t kill it.

And then I’ll go out on the porch and bear witness to the night, a night few will ever experience and few would want to experience. I look up at the stars, and notice that they seem to be gradually fading out. I thought this was poor eyesight at first- but I used my binoculars to confirm that yes, various stars are disappearing. Phecda, the star on the bottom of the big dipper nearest the handle, is gone. Absence where it had been. The vacuum of space.

That soft, lovely blue beacon with its four corners and pale countenance is only one more thing lost, and anytime I ask someone about it, about where Phecda’s gone, they don’t know what I’m talking about. Because nobody cares anymore, nobody looks at constellations. Certainly nobody around here.

In the days, there’s another thing you don’t know about Petomele. In the days, the skies heat up and boil. There are times- although these rare instances never coexist with anyone besides myself being out- when the clouds begin to form little pockets, little dots and speckles, as if someone had put a kettle on, and all five trillion molecules of water vapor in a cumulonimbus decided at once to start seething and frothing like the torrent against the Demeter.

And they move too fast, these clouds- coursing over each other with too much rapidity for what are supposed to be light, fluffy things- they always seem in such a rush to get somewhere, to do something, some grand design that continues to elude me. And still I watch and wait, out on my wicker chair, binoculars pressed tight over my weary eyes. I’m tired, so damn tired, yet the skies wear on.

You don’t know Petomele in that it fades out, sometimes, becomes monotone, and the buildings become lifeless, all the trees die at once and the roads give way to an ethereal mist that surrounds everything and shrouds us all in solemn introspection. When this happens- when the mist comes on- none of us leave town. Because we could keep driving on the road out and never get anywhere, and fail to return.

You have no idea what it is to stare out the front door into the path of an oncoming twister as it plows towards you and everything you hold dear, plummeting for an unfathomable length from an angry stormfront. You don’t know tornadoes until you’ve seen them like this, lashing at your skin, a sickly vomit green in the air, your livestock decimated. These are Petomele tornadoes, they arrive without warning and depart just as soon. They live.

You get the impression, living here in Petomele, that something has gone deeply wrong, that somewhere in our past we refused to learn something, internalize something, make anything of ourselves. Yet we persist. We have no right to stay out here, separated from the world, yet we do. Somehow, we’re here. I’m here.

And here in Petomele, while the stars blink out one by one and the mist descends and the clouds keep rushing over each other, covering the sun and killing the crops, you have time to sit up late and think, Think long and hard, about a variety of subjects- the only ones known to you in a world that grows further removed by the day.

I think about her as the twister neared and I fled inside for the safety of the basement, failing to open the screen door and grab her wrist, pulling her into the house with me. I don’t recall what split-second decision caused me to leave her out there. Perhaps I thought I didn’t have the strength. I probably didn’t.

You remember things like that, how the human body looks one second before it’s warped into something completely unrecognizable. A face as it vanishes into that sentient wind, less terror in it, less pain, more awe. Awe at the prospect of what it’s about to transform into- into the sky itself, pulverized into infinite permutations, a kaleidoscopic fractal nightmare. I did see that face, right before death came crashing in and broke every piece of furniture and dismantled our humble abode with every ounce of strength and fury it could muster.

One second, and then it’s gone, like so many other memories, a snap and it’s no longer there, having evaporated silently into the tempest. And now the days are quiet, and long, and we sit outside while our windows go out, one by one, until the only lights visible are the lights on a lone rig out on Highway 423.

No, you don’t know Petomele.