(Originally discovered at Nawrak Terminal 41, Qra. 1793)

It was accepted unconditionally by all in the Electric City that the current would flow- and therefore it did, regardless of source.

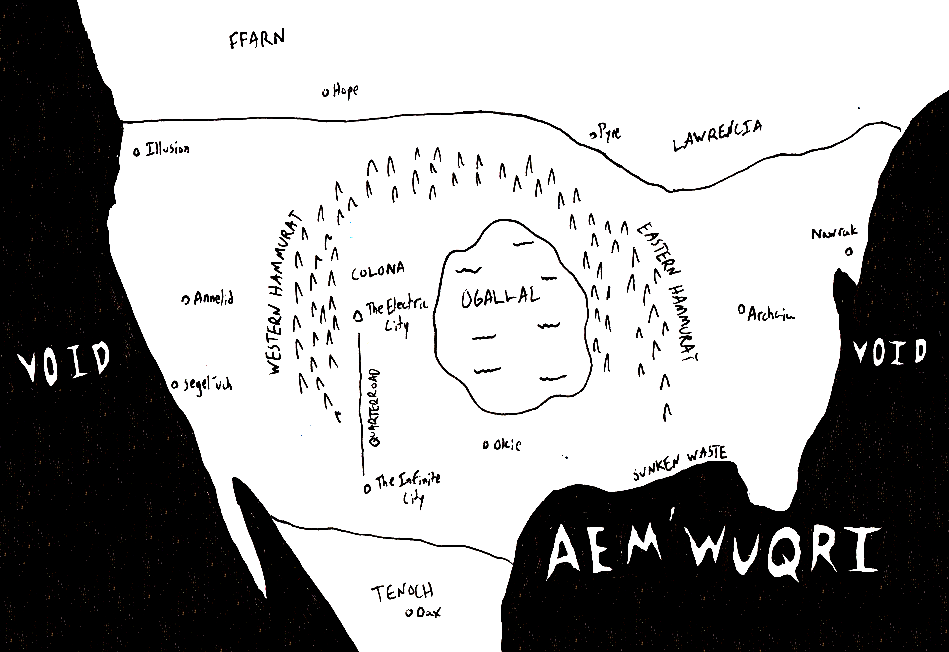

This faith was put through trial across the centuries, yet it held, an indomitable mark upon the Aem soil, a mockery to the forces beyond that they would not prevail. And on the lavender fields, the phenomena were scarcely made note of- such that, over time, the people grew languid and flippant of that which they did not require knowledge of.

Their mathematically defiant neighbors in the impenetrable waste, lit forever at noontime, were connected to the Electric by the Quarterroad, a winding structure which transferred carriage and mercantile alike. The citizens of the Electric avoided the Infinite whenever possible, for their frail, transparent bodies were tested by the moderate heat of the Infinite, and the people of the Infinite avoided the Electric in kind for its cold indifference.

As such, by Qra. 840 the Quarterroad had been neglected beyond repair and was consumed in places by the weeds, making contact between the two desolate outposts unthinkable. And so the people of the Electric made do as they always had- their eager thirsts quenched by the limitless fountain which harried forth from the springs and inlets.

Then came the golden age- the era which most ascribe to that strange Metro. A world of sights and colors, elemental gases discovered which could be contained within a tube, silicon craftsmen who discovered alchemical blends and wired concoctions unlike any which had been seen- and they grew overconfident in their technical wonder, as the City grew from a modest thing to a delight and an excess, a proud bastion.

There were the elders, who sat on their chairs of transistors and argued for the repair of the old roads- the rediscovery of new places, a return to the age of exploration- however the Magistrate and his cabinet were not concerned with what lay beyond, they were only concerned with probing ever deeper into the resources at hand, which were plentiful and lavish.

The City could be viewed with a Monocular from a distance of 40 Verets, if one were to account for the atmospheric distortion of the horizon. On a clear night, travelers on the outskirts of the Metro would rely on the positions of the red beacons and the glittering deluge to orient themselves amid the deep silhouettes of the Eastern hills.

The opulent years wore on, and the City became reliable and dependable- lightning plummeted from the violet skies towards the spires and rooftops, smokestacks billowed soot which contributed ever further to that deepening night, and the people forgot what day had ever been, for the poles and wires drowned out all naturally occurring forms of visibility. Beneath the cavalcades and promontories they walked, unaware of the circumstances which bore them.

Ingestion of live current was recommended by the Cabinet as a source of good health, and frequently it was seen also as a social custom, as a means of determining who was of what station- how to properly cut a wire, drink from it, and so on. And the organs of the people, visible through their bleached transparent skin, responded in kind with vibrations and flashing patterns, which were purported to hold deep spiritual meaning.

The perimeter, as always, was held close by a team of lamplighters who went out every dusk to ensure the beings sequestered in the Hammurat would not protrude into the lavender fields. Signs were posted advising residents against leaving, and these signs leaned against the lamps on rusted poles and were seldom heeded, and those who did not heed them always paid the price, their screams echoing throughout the moon ivory valleys and dips of the Western flank.

By this time the Infinite had become a mythic piece of folklore, told to children around the picture box, and nobody had the means of traveling there. And so generations of residents were taught that they were the only variant of their species, that none like them existed in the lands beyond, which were the domain of the horrid and the malformed, a breeding ground for the undesirable waste.

This was reinforced among the populace by the wretched noises emerging from the divots and caverns, sounds which drained batteries and slowed ionic friction. Devices were installed to reflect these noises towards their source, yet every now and again one would make its way along the City’s commercial area and instill terror among the shoppers, and the garish billboards would abruptly flicker off, which was regarded by all as a horrible omen.

The advertisement of Charles The Cat, in particular, which loomed high above Faraday Avenue, was regarded by many as an iconic landmark, and special care was taken to direct the current towards it, such that it would never fail. A sonnet commonly spoken by the sages on rainy afternoons went as such:

I looked above and saw the feline grin

A gesture ‘neath the moon, it heard us come

It feeds our ilk, our families and our kin

And elongates its shimmering red tongue

I heard death far away, yea, and it cried

For all who would grow blinded by its call

I saw my land in ruin, it had died

The current failing some, then failing all

Yet Charles stayed alight throughout the death

For nothing could discourage that damned cat

Its eyes pierced through till I took my last breath

A symbol of a world growing fat

If this should not become the state of things

Then there is hope, and hope’s all we can bring

“I never grow weary,” the magistrate would affirm, swirling a battery around his tongue for invigoration, pacing around his ornate office with his yellow cape swishing behind.

“Mine is a station of honor and of duty, and as your public servant- yes, your representative- I will continue to occupy it, for as long as our children their children and theirs after them continue to drink from the track and wander the same conduit in search of meaning, I will drink with you- yes! Drink plenty, drink what is good!” And he would appear to the masses on their picture boxes, and toasts would be raised in the direction of the Mag, splendid swirling cocktails of acid and alkaline.

The lamplighters were of a different mind, however, for when you exited the perimeter of the city, which were marked on all sides by a tangle of bundled cords, which emitted a frequency designed to keep the filth at bay, you would feel a chill come over you.

The chill was gradual, yet palpable, for unlike in the Eastern hills, which at least carried a vestige of Colona civilization to them, with their sparsely arranged shacks and loose network of streets, the onset of the Hammurat was marked with a pale stillness, and a lingering quiet- and the lighters could only turn back toward the City, positioned towards what they knew, avoiding the terror at all costs, lying to themselves in regards to its potency.

Through the pale sheath of the helmet which comprised the standard Lighter’s uniform, the Hammurat’s bony talons were dulled, even as they stretched upward toward the sky like piercing needles all the same, and the silence was broken only by the lighting of wicks in the crisp evening, and once this task was completed, the lighters would run as a group back toward the perimeter and drink heartily to erase their memories.

On one occasion, however, in the nine hundred and twenty fourth year of the common period, one specific team of lighters encountered the unthinkable- an outsider.

The outsider appeared at first to them as a lanky thing, sparkling pupils from past the fog, near a pile of granite slabs- and they cowered in slavering fear for they were unarmed and had neglected to bring any rays. As the thing drew closer, they withdrew several Fractif-Verets and let forth a specific tone from their singed mouths, a tone developed from evolutionary necessity, a tone meant to alert the public and ring a mechanism of alarms at a moment’s notice.

The outsider stood completely still, breathing heavily, and the lighters sat equally motionless with the hope that the outsider would not harm them given their weakness. All the while in the city the great central tower’s computer detected the tone, distant though it was, and a squadron of officers was released for investigation.

The officers mounted a nearby hill and dispatched one agent to apprehend the intruder. They pulled out their monocs and refrained from any sudden behavior, and the silhouette in the void abruptly doubled over as the agent hit it with a refractory beam and its defenses were weakened.

“Good, Drensey,” they whispered. “Bring it here. We’ll take it.”

They then dismissed the team of lighters, several of whose hearts were quivering with the utmost rapidity, their neurons sending blue signals of ice-cold fear as they shielded their eyes from the entity. The officers wrapped the unconscious thing in electromagnetically protective material, hoisted it upon their shoulders- they could scarcely handle the mass- and began the long trek back toward the flickering spires and avenues of the City.

Faion awoke to the scent of burning copper, a metallic slab to which she had been chained. The Magistrate stood at the far end of the room, his cloak rippling hesitantly in the breeze. It was midnight and as such the central Clock began chiming its distant toll, which rippled throughout the Metro. Faion could tell that her forehead was trickling with blood.

“It’s awake,” he noted dryly, tapping his temple. “For all we did to it, it’s awake.”

“Who are you?” she whimpered.

“I’m far too important to be concerned with you,” he replied. ‘They count on me for their survival, they rely on on me, year in and year out, to provide for them- and here you came, to paint me in the worst continued presence here- your status as a threat to my people- puts me in a mood I can’t begin to describe.” He leaned in and Faion got a good look at his visage- a vivid chartreuse, pocked by scars and the remnants of an adventurous youth on the outskirts.

“You didn’t answer my question,” she spat through her lips.

“You can call me Oekser,” he responded. “Though it hardly matters, that’s only my regal title. I’ve had many. Now- who are you? Where did you come from? An illusion, sent to us from some mind-warping predator so as to weaken our defenses? A cave sorceress? Why, look at you- your skin is opaque.” He said the last with visible disdain, raising his eyebrow in feigned shock.

“I come from Annelid,” she cried. “Annelid, beyond the Western flank. For thirty days and thirty nights without rest I have journeyed here, up the far slope and down its gulf, along infinite deserts and long-abandoned depots I have persisted. Only to find myself here, subdued by your people without warning and now confined like an animal.”

“And an animal you are!” Oekser shouted, holding his hands toward the ceiling. “An animal without purpose, without answers, desperate for guidance! Annelid! What a place! Dreamt of by fools, mentioned in apocryphal texts with no basis in fact! We have sent armies into the Hammurat! None have returned! And to think that YOU would return- this is heresy! Outright!” He tapped the floor with his staff, twirled it between his gnarled fingers, then brought it down onto her knee. Faion grit her teeth in pain.

“Animal,” he repeated. “No instinct in you, no sense. How could you traverse the range without a constant supply? Some form of stored energy? No, you lie. You try to deceive us, but the truth will come to pass, and you will only then be capable of answering to yourself.” He circled her like a crooked vulture, as she sobbed quietly, tears streaming down toward her ears, incapable of speech, and then he dimmed the lights with one svelte move of his forearm and left, the iron gate swinging shut in his wake.

Faion attempted to bring her mind to happier times, to arrive at a point of clarity amid the turbulence of her rushing brain. Annelid. Yes, she was from Annelid. She knew she was, because she had come of age there, even if today it seemed like a fragment of a murky dream. Annelid, beneath the purple skies, plains of waving grass and the small thoroughfare. A beacon of stability and peace in Aem. So unlike this place...

Spotlights from zeppelins drifting silently outside the window came to rest on her eyelids, and still she ignored them and focused on the breeze, the butterflies drifting from petal to petal, the simple aroma of home cooked bread in the oven. Yes. Annelid.

Far above, in the master chamber, surrounded by panel upon panel, Magistrate Oekser wound his hair around his fingers and stared out into nothing, his mind slowly unraveling at the majesty of the world he found himself in. It was beautiful in every way.

The trial was broadcast from every large window display and held in the Great Hall of Justice, its neon tubes emblazoned with the motto of the City and a graphic of a stoic eagle gnawing the head off a smaller herbivorous bird. Faion looked down at her feet as the officers paraded her around the crowd, giving every agency a good look at the being which had eluded description, and numerous families at home prohibited their children from watching lest they witness the freak with the obfuscatory complexion.

She did her best not to pay direct attention to the way their organs pulsed and writhed in those crystalline sacs, how their eyes burrowed deep into her psyche and made her feel as if she had no secrets. They were victims as much as she was, she told herself. Victims of a cold environment who existed within a prismatic veneer, and if she could put her standards aside she could view them as people, like herself, who had gone through far more than she had.

She tilted her head back and caught a glimpse of Charles’ awful stare before a protective material was once again wrapped around her head and she was forced into the antechamber of the hall, where wires wrapped themselves around marble pillars. Wires, she had found, were present everywhere, in every variety and delineation, as common as plants, and it was then she realized there were no plants to be found- none whatsoever- within the perimeter.

The crowd’s shouting decreased as they proceeded beneath the sterile gray blocks of the structure, echoes all present- she could smell flesh burning, burning because they never considered turning their current off, all while the wires hummed in unison, hummed with the vibrancy of a hornet’s nest, thousands of minds as one-

They stopped before the podium.

Magistrate Oekser unfurled a scroll, examined it closely, smoothed his hair back for the sake of the agency cameras which followed his every move for public record. He was tense, although he hid this well beneath his swinging robe and respectable demeanor, emitting a frequency of unparalleled confidence and charm.

“Case 90475,” he read aloud in a calm baritone. “Entity from the Hammurat, second recorded during my tenure, first having been a feral wolf-thing.” He gestured toward the stenographer, a pale citizen whose glasses cracked aloud as she hit the keys of her typing apparatus, every click receding on into the farthest recesses.

“What is your purpose here?” he inquired.

She did not reply.

“Purpose!” One hit of the gavel, as furious as his handling of the staff, and she felt pain- though whether this was psychosomatic or some variety of sympathetic sorcery on his part she couldn’t make out. It was awful, however- a ceaseless grip on the scalp, as if she were being pulled around on strings. Her hair ascended.

“Purpose, for the last time! Purpose, or you shall die here! Is that what you want?”

“To warn you.”

“To warn us? Of what?”

“I didn’t know you were here, when I left,” she said, dropping to her knees. “But I do come to warn you, now that I know you are here. There is something out there, waiting for you. Not me. But it’ll be here soon enough, you’ve wasted so much time. It’ll be on you, and there’s no way you can hope to defeat it. I wanted to give you time to evacuate, to prepare your defenses and shield your people- but you won’t allow that. You’ve cut off the very circuit you rely on, to use your own vernacular.”

“Your appropriation of our vernacular is unappreciated,” he smirked. “Although given we have arrived at this point, and the purpose of this ritual is to discern all that may be, please elaborate as to the nature of this creature. Our rays will subdue it, and we will bring it to our mercy, as we have with you.”

“No, you can’t,” she remarked calmly. “A red thing. A cloud of fury. It destroyed Annelid. It’ll destroy you, because it feeds on rage and fear, and that’s all you have. Obliterate you to your merest components- atomize you for the worms to gorge themselves on.”

Oekser reclined in his seat, rolled back, and laughed uncontrollably at the cameras, his grin widening double, his eyes held open by unseen toothpicks, pointing at Faion with his staff and giggling like a maniac, such that even the most experienced agencies were disturbed enough to denote a shift in his temperament.

“She lies! Can’t you see? She lies- even if this thing were real, there can be no doubt that she’s in league with it, a spy, some kind of agent-”

“Suppose she’s here to help us,” said one member of the Cabinet.

“No!” he roared. “Lies! Deceit and falsehoods to make us look foolish! Why, she’s alone! To even give credence to her narrative would be to imply that there ARE further entities beyond-”

She stared at him and made direct eye contact, and a tangible jolt passed between them, and she caused him to feel colder than he ever had, sub-frigid to the deepest conceivable level, a horrible sensation. She had power, and he could not allow that. It was time to end this game.

“To death!” he shrieked, flapping like a raven. “Death to the creature! Summarily!” And he brought down his gavel as the crowd outside cheered, ticker-tape circuitry raining down upon them from the prepared fixtures above, a multitude of happy smiles in energized rapture at the apparent renewal and continuation of their status.

“Execution?” murmured the cabinet, scratching their wizened heads. “We can’t have such a thing. Our resources are finite enough as is- the current can’t be diverted toward the chair.”

“It will be.”

She waited. The thing was her only real constant, in that she was certain of its imminent presence, its looming threat. In her small contained cell she looked out between the bars and caught glimpses of the current running circles around the Metro, flashes of voltage unconstrained by reasonable temperaments. She was sick, she thought, sick beyond measure, because the radiation in this place was slowly disintegrating every cell in her frail body, which had been reduced as it was by the wastes and the horrible weather she had endured on her journey here. And now- a meaningless death. To match a meaningless life.

How odd, that this place, so much larger and splendid than Annelid, should fall to the same vices, the same corruption, the same pattern- it were as if these patterns repeated themselves, over and over again, in variations- she caught glimpses of some kaleidoscope, like a wheel cutting through the sands of time and space- and then it was silent again, save the ceaseless surging of the wires, and she was grasping her knees and lying in the corner on the frigid stone.

Around the corner, footsteps approached. She prepared herself, adopted a stern resolve and accepted her fate, and the fate of the City, try as she had to save it from harm. Rather than one of the officers, though, there came a tiny, hunched figure- a deep amber, nearing the end of his life, by the hooks of him, frayed and with shorts throughout his veins.

“It’s alright,” he said from beneath a tepid shroud. “They let me in. They don’t suspect a thing.” He wheezed, crawling in her general direction on all fours, and Faion saw that beneath the dark shroud he was covered in rags- doubtlessly considered a leper among the populace, with one gaping eye socket and several missing fingers.

“It’s alright, humbuzz,” he said, reaching forward to clasp her hand, which was clammy and tepid and shaking with uncertainty. As he did, a warm charge passed from him to her, and suddenly she felt warmth- a sensation she hadn’t felt since her departure.

“What-?”

“It’s alright,” he said, producing some mechanism from a satchel. “I’m a sage. One of the mnemonic variety, we who tell the tales of the world gone by utilizing eidetic memory. They trust me unconditionally, don’t give me much credit beyond the capabilities they know I have. As for the capabilities they don’t know I have- well...” He clicked a button on the gadget and it lit up, producing a blue shade which glinted off her nails.

“This will subdue them,” he said. “You’ll make it. Go, now. Future songs will tell of this moment. Use that fact to inspire you.” A chuckle, then a retreat into the stillness and a slow evaporation into invisibility, leaving the door of the cell unlocked. She rose to her feet, making a conscious attempt not to fall over, then in one smooth motion she extended the device at arm’s length and ran forward, disregarding anyone or anything in her path.

One smooth bolt, energy which hadn’t been seen on the Grid in years and which could power fifty households, produced through sheer will, akin to the will which the citizens of the City had been subconsciously producing through their belief. She cut holes through the sheets of protective material on the outside of the holding compound, flashed past the desk in the foyer, cut through the steel gate like butter and her legs kept whirling like a bandsaw, carrying her out into the night and onto the streets and though she turned heads wherever she went, nobody bothered to stop her. It was too late.

She would head south, along the Quarterroad, use it as a general guide towards her destination, wherever she intended to go, and maybe the red thing would choose to follow her rather than target the city and perhaps it wouldn’t, but either way her death would achieve nothing. Before the siren could be activated, she was gone, and as far as anyone in the City cared, she was dead.

The Magistrate stared out into the swirling cornucopia of excess, every laser and beam activated, all windows lit, moths scurrying around them, and his eyes darted from one direction to the next as his thoughts, little insubstantial thoughts, raced along the same simple track, over and over without resolution.

The Hammurat waited beyond, saying nothing but meaning everything with its very existence, its constant assault on the senses, its desecration of everything that was good, and its silence only enraged him more, such that he was caught in an indescribable ecstasy.

Nothing came from them.